Source: Dionne C. Monsanto

The following post, a love letter from a mother to the daughter she lost to suicide, is the latest installation in NewsOne’s special series, An American Crisis: Black Child Suicide. It contains detailed information about child abuse and suicide. Please be certain to ensure any support you may need in reading it, and please be sure to make use of any and all resources NewsOne has complied for you or any of your loved ones you may have concerns about. If you or someone you love needs support right now—-or at any time—please dial 988 or text 741-741.

The morning of Wednesday, June 29, was so beautiful. The sky was so clear, so welcoming as I stepped outside at 6 a.m. It whispered, it’s a new beginning, for the entire walk to the subway I rode to get to my 6:30 yoga class. It was my ritual, taking that class. It was my time to center, to balance and ground myself before the rest of the day rushed in. I had an important meeting I’d have to rush home and prepare for immediately. It would work. My son, Sule, 18, born of my relationship with my college sweetheart, had a summer internship with Morgan Stanley and would be gone by the time I got back. So would Eric, 14, my bonus son/cousin who would already be at school for what was always his favorite day–the last one of the school year. It would just be me and Siwe, my baby and the only daughter.

She was 15. Her father, Paul, and I divorced when she was just 2. He’d grown mean in our short marriage, or rather, he became who he really was. Siwe was the singular blessing of that relationship, and she and I were together more than we weren’t. Siwe had started homeschooling with the support of the Department of Education. She was gifted beyond the telling, but lived with depression and an almost crippling level of social anxiety. Both had been spiraling year-over-year since she was in grammar school. My baby. So desperate to fit in, so afraid she never would. But I had every hope that today was the start of a new season for her, for us. The meeting I had was with a school I was so certain Siwe would thrive in. It specialized in engaging young people who were exceptionally gifted and who were also challenged by their internal emotional landscapes.

Siwe, my baby born on March 8th, International Women’s Day, this is my love letter to you.

When I made it back to the house at 8:30, Siwe was still in bed, fast asleep. I nudged her awake, reminded her quickly about the meeting I had and her date with her sister, Ayoka. She was Paul’s daughter from a relationship that predated ours and Siwe loved her. She lived in Texas then, making their time together all the more special. That June 29, they were going shopping for clothes that Siwe needed for our family vacation in August – a cruise to Bermuda. Siwe had picked out the boat we’d be taking! I wasn’t surprised that my baby girl was grumpy when I woke her, but she got up anyway. I quickly showered and changed for my 9:30 appointment at the school. I kissed Siwe on her forehead just a little bit longer than usual. I really wanted a hug; but reading her cues, I let the kiss suffice and headed downtown to the new school where I was on time for my 9:30 with the principal.

Source: Dionne C. Monsanto

She was lovely. Just the choice she made to meet with families rather than having a surrogate do it demonstrated her care about ensuring the school’s balance. She was intentional, knowing the kind of safe harbor young people needed to learn, to grow, to just be in. I wanted Siwe to be accepted there so badly, and even more so after I’d toured the school and sat down in her office to discuss my precious daughter. But as soon as we began to speak, my cell phone began to buzz. I’d ignore it only to have it start buzzing again. I’d checked to ensure it wasn’t Siwe, and it wasn’t, but the interruptions kept coming. The principal in her graceful way, encouraged me to answer and I did, finally. I did, but was annoyed. I mean, what was their problem? Weren’t they getting the message by me not answering? Didn’t they consider I was doing something that was important enough to require my full attention? And honestly, there was nothing more important to me that morning than getting my Siwe settled in a place where she could find her way, find her tribe. I answered the phone.

It was my next-door neighbor. He began speaking as soon as I accepted the call and his voice yanked me out of my seat. There was this urgency in his voice, which while shaky, also left no room for questions: get to New York Presbyterian Hospital immediately. I was at the office door the moment I heard his voice and whispering an apology over my shoulder to the principal. Within 2 minutes I was in a cab speeding uptown. The hospital was three blocks from my home. And it was strange. Sitting in the back of that car, the feeling of urgency shifted to a feeling of annoyance. Frustration. Whatever I was rushing to had to be about Siwe. I’d been here before. I knew I was facing another attempted suicide. Siwe had been hospitalized several times for suicidal ideation and three times for actual attempts. Siwe. Siwe. Why won’t you let me help you? It’s all coming together. The vacation. The school designed specifically for you and children like you. Baby, I’m on your side. I listen to you. I got you. We got this. We can do this!

You lived beyond borders the whole of your life until you no longer could.

The cab pulled up to the hospital and I took a deep breath not wanting my frustration to show as I headed in and to Siwe’s room. How many times had I done this walk? First stop, security desk. Next, give her name. After that, go to her room or the ER. But wait. Something was off. Security was saying that they didn’t have her name. Had my neighbor been confused somehow? I told the officer that I was called by someone close and told to get here immediately. Oh, the security officer said, adding just as calmly, must be the Jane Doe.

What? Jane Doe? Are they crazy? My daughter has a name. Siwe Monsanto. Actually, Busisiwe Monsanto. Her name meant blessing. As a full name or a shortened one. Blessing.

The security officer ignored my confusion and just said, Well, be that as it may, she had no ID. So for us she’s a Jane Doe. And with that, I was sent to the room I assumed Siwe had been screened in. Where the hell was she, anyway? I needed to see her and told the social worker and police detective so when they entered the room the social worker began questioning me. What had been Siwe’s mental state? Could I prove who I was? Did I have a picture of Siwe? I wanted to shut that social worker up badly. She was so perfunctory. Weirdly, the detective was gentle. But I just wanted to finish so I could finally get to my child. That’s what I was thinking when the detective said carefully, almost kindly, that Siwe had jumped off the roof of a building near our home. I was silent because, how do you respond to that immediately? The officer replaced the hard quiet with hope.

She’d survived!

Now I really demanded to see Siwe, but they said they were doing CAT scans and other tests. The detective then told me what I already knew. It wasn’t an accident nor was she attacked. Siwe had attempted to end her life. That I knew and nodded accordingly as his phone rang. He was agitated. Why? Where’s my daughter?

I was rushed out of the room. It was time to see my daughter, but why are they taking all of these extra steps? I knew what I was facing and had been readying myself. The harm had to be terrible. I prepared for the broken bones, the blood, the bruises and took a breath. They led me in to see her.

More accurately, they led me in to identify her. I was identifying the body of my 15-year-old daughter.

This is a love letter

Source: Dionne C. Monsanto

Siwe, this is a love letter to you. You, born on the exact date the doctors predicted: March 8, International Women’s Day. You lived beyond borders the whole of your life until there came a summer Wednesday when you no longer could. No freedom to move about made you feel safe that day. No boundaries did either. My Baby. My Siwe, who always moved so fast and so powerfully. Fifteen Siwe years is like 50 other people’s years.

My neighbor’s voice left no room for questions: get to New York Presbyterian Hospital immediately.

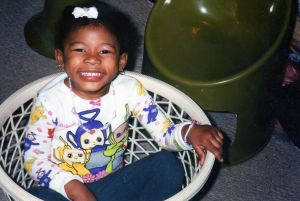

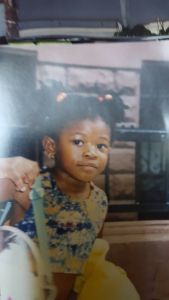

You stood in your crib at 4-and-a-half months. You walked at 7 months. By 2 you were having full-blown conversations, making clear arguments. You could stare me down. You took over the whole house when you arrived. The boys were totally lost. What were they supposed to do with this smaller-than-them girlchild, who nevertheless, insisted on doing everything they did. You always won in those efforts. The most determined baby ever! Siwe the Baby was in charge. You demanded a library card when you were 4, able already to write your full name. Took out books and mocked your brothers—who liked to read—but you didn’t think their books were as grown up as yours. You set learning goals for yourself and nailed them again and again. You tutored your friends. You were always in at least the 90th percentile scholastically. What couldn’t you do? You sang beautifully, danced beautifully, played the violin, cello, acoustic and electric guitars, and published poems in English and Spanish. Siwe! You weren’t even in high school yet! You were 13 when you started on your novel and met with an editor, illustrator and publicist! We didn’t have the time to work through the contract, but it was coming.

Siwe. Siwe. You were the smartest, friendliest, happiest little girl until you weren’t.

Everything is true, everything is a lie

Everything I’ve written about my daughter has been entirely truthful and entirely dishonest. People did see the happy, friendly child out in the world. I saw the baby at home who had long crying spells that worsened exponentially by the time she was 7, the year she turned inside of herself. She came home one afternoon that seventh year of her life from visiting her father–he had weekend visits and lived half a mile from me. No matter how much I tried to understand why she was different after that visit, nothing made sense, and Siwe wasn’t talking. Neither was Paul. And then he told me what he’d known and kept from me for at least eight weeks. Siwe told him that she’d been molested in a diner by a random person one afternoon when they’d been out. And Paul waited to share the news until he was what? Good and Ready?

I was furious. How could he keep something like this from me? Our daughter deserved our support. I called the police immediately and they were able to identify the man Siwe described to them. He had a history. Other small girls. Maybe other small girls who had crying spells like mine. But there was nothing they could do. The man had jumped bail and had been in the wind for months. I made sure that Paul was only allowed supervised visitation for a long time afterwards. How could I allow a man with such poor judgment to be with her alone? Hell no.

I hadn’t fully unpacked all the reasons I’d put him out years ago. If I had, would they have been enough for me to keep her from them? Paul was mean. Not at first. At first he seemed to be an amazing listener, someone who cared about the details of my life, was actually interested in them. He was physically beautiful, a fitness model. But that hadn’t drawn me to him. I was drawn to the very skills he had that should have made me run from day one. It took the first two years of Siwe’s life for me to work through his emotional abuse; the body shaming, even when I was pregnant with our daughter. You’re too fat he would say, unattractive, he would say. Get to the gym, he would say. I don’t know how I summoned the strength to get him out of my house finally. He’d worn me down so badly. But not completely. I was there, still inside myself and he was now gone. In Paul’s absence, I became stronger. Found real love. And in the beginning we seemed to co-parent well. We were so civil with one another that most did not know we were not a couple anymore. But we weren’t and Siwe was our only reason to engage. And then she became the reason we had to completely disengage.

It happened on a winter Sunday when Siwe was 11. She’d gone to spend the weekend with Paul and suddenly she’d snuck out while he was distracted and began to run from his apartment to our house. An older Black woman, an angel, driving by saw her: tiny brown bird of a girl in pink pajamas, pink track shoes and no coat. Seeing Siwe, she stopped her car, worried. Why was this little one out here alone and in just pajamas? There was still snow on the ground! But unlike when she was 7, Siwe told immediately. She said to the woman, the angel, that her father had touched her private parts and she was trying to get home to me. This angel wrapped her coat around my daughter, called 911 and stayed with Siwe until an ambulance came. I’d been calling her anyway to check on her. Finally her phone was answered. By a cop. I headed to the hospital.

Siwe lived with depression and an almost crippling level of social anxiety.

Paul was arrested that day. The social worker attached to the case, a Black woman, broke protocol and came to see me afterwards. I was with my partner, Roger, who carried me through that time and the times I didn’t know lay ahead. The sister took a breath. She’d just come from speaking with Paul and detectives. She said that when police confronted him about what happened between him and his 11-year-old daughter, he didn’t deny it. He was actually pretty calm when he said, “She acted like she didn’t like it. But you know how women are.”

Nearly a year passed before the case was adjudicated. Paul was sentenced to five years. Up until that point he was free on bail, still living 10 blocks from us, from Siwe. We had an order of protection, but it was as still unbelievable to me—as was the five-year sentence, which was apparently the norm for a crime like this committed by a person who did not have a previous record. They called him a Level 1 sex offender. He was bad, but not too bad because after all, he didn’t penetrate her. Just some touching. Just.

With Paul living near us while he was on bail, Siwe’s depression and anxiety continued to grow, even as he was remanded and began his sentence. And then after four years had passed, I was notified: Paul wasn’t going to do even the five years. He was getting out 12 months early, they said. Good behavior, they said.

I never told Siwe about the change in the length of time he had to serve. But I think she knew. She knew the original sentence. She could do the calculations. Even if he’d been forced to serve the five years, it still wouldn’t be long before he got out. On June 29 of the year she died, Siwe knew time was growing short.

My daughter’s voice

Siwe, I am writing you a love letter.

Source: Dionne C. Monsanto

I left the hospital on June 29. I couldn’t tell you what time. I remember trying to understand the world after seeing you lying there but not being able to. I remember seeing people, cars, buildings through a mean, heavy fog. Was it true that I could make out those people acting like something, like anything, was normal? It was one of those nightmarish funhouses, Siwe. The kind where everything is almost the same and everything is entirely different all at once. Why do they call them funhouses anyway? They’re houses of terror. The world unfolding without you that day, for days, for months and for years, was a world that shapeshifted. It was a world where nowhere was safe. Was this the world you knew, Siwe? My God.

I try to, but cannot, really even remember the planning of the memorial, all people who helped our family immediately after your death. I can only remember, clearly, the shame.

How could I have ever chosen Paul? What kind of mother was I? What kind of woman?

And then the answers came to me. You came to me, Siwe. You. I was the kind of mother who had always been determined to live in honesty mostly because I had a daughter who demanded it. You needed the truth, Siwe. Needed it heard. You needed me to live it and speak it all at the same time.

I am speaking, Siwe.

My daughter was gifted beyond the telling. She could read and fully write by the time she was four.

Our Afro-Caribbean family, you know this, was not one to discuss any personal matters, least of all mental health matters. But I’m speaking, Siwe. Your courage lives in my throat, and we are creating a new design for our family.

Siwe, I came from a place where secrets were polite and something like suicide only lived in headlines about some famous person we’d never know. I came from a place where the prevailing wisdom was that Black people did not kill themselves. Suicide could never impact my life or yours. I believed that until it was impossible for me to. So I’m speaking, Siwe.

I know now what I didn’t before. All the flaws in systems for children, in healthcare. I did the best I could with the information I had, and I know so much more now. I’m speaking, Siwe, so other mothers will know more.

After your first suicide attempt I didn’t know who to talk to, what to say, or how to protect you once you came home. And then, I don’t know? Did it become almost a routine? You harm yourself, end up in the hospital, come back home. I swear, and I know it doesn’t make sense, but I swear I somehow thought you would live with depression and manage the self-harm. I swear you dying by suicide was not a possibility.

So I’m speaking, Siwe. I’m telling other mothers across this country and across the globe that they were not bad mothers. I was not a bad mother. I was and still am, a good mother. The choices our societies make are bad. Childhood has always been a dangerous venture, especially here in this country. Now I know, Siwe, now I know. You taught me so much. You’re still teaching me.

You gave birth to the woman I’ve become.

Remember, Siwe, when you wrote that article where you said the problem with adults is that they tell kids they can be anything they want to be but they never seem to model that themselves? I come back to that article all the time. I know you couldn’t stay long enough to be whomever you wanted to be. I’m trying, Siwe, with every breath, to do that for you. For me, but for you. You can’t so I have to. And baby you would be proud. I now set clear boundaries; ask for help when I need it; surround myself with people I truly want to be around, not people I can barely tolerate. I choose small and large moments of joy for us, Siwe. You’re the face of those moments. The clarity when I look people in the eye and say I’m Dionne C. Monsanto, mother of Siwe. Listen closely as I speak. You’ll hear something honest. You’ll hear something helpful. You’ll hear the voice of my daughter.

Siwe.

International Women’s Day was a Friday the year you were born. This year, March 8 is also on Friday. This is your day, Siwe. I sing your name. I sing thank you, baby. I sing I love you. I love you. Again and again and again.

Mommy.

Dionne C. Monsanto is a bestselling author, yogi, speaker and holistic wellness coach who creates the space for her clients to realize their goals and build better versions of themselves. She sits on the National Chapter Leadership Council for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP).

If you or someone you love needs support right now—-or at any time—please dial 988 or text 741-741.

Resources

Book Recommendations:

Black Pain: It Just Looks Like We’re Not Hurting, by Terrie M. Williams

Description: The legendary celebrity PR executive delves into the emotional and psychological challenges faced by Black individuals, offering insights into how these

Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice, by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins and Ann Hazzard

Description: Addresses themes of racial injustice and provides guidance for parents on discussing difficult topics with children, including emotions and coping strategies.

Age Range: Children, recommended for ages 4-8.

Video Recommendation:

“Teen Mental Health and Suicide in Black Families“

Description: This PBS documentary explores the unique challenges and experiences surrounding teen mental health and suicide within Black families, offering insights and resources for support.

Age Range: Teenagers and adults, recommended for ages 13 and up.

Website Recommendations:

https://www.crisistextline.org/

SEE ALSO: