The Love Of Nikki Giovanni, Poet, Mentor And Friend

Nikki Giovanni’s Insistent Black Love: A Memory

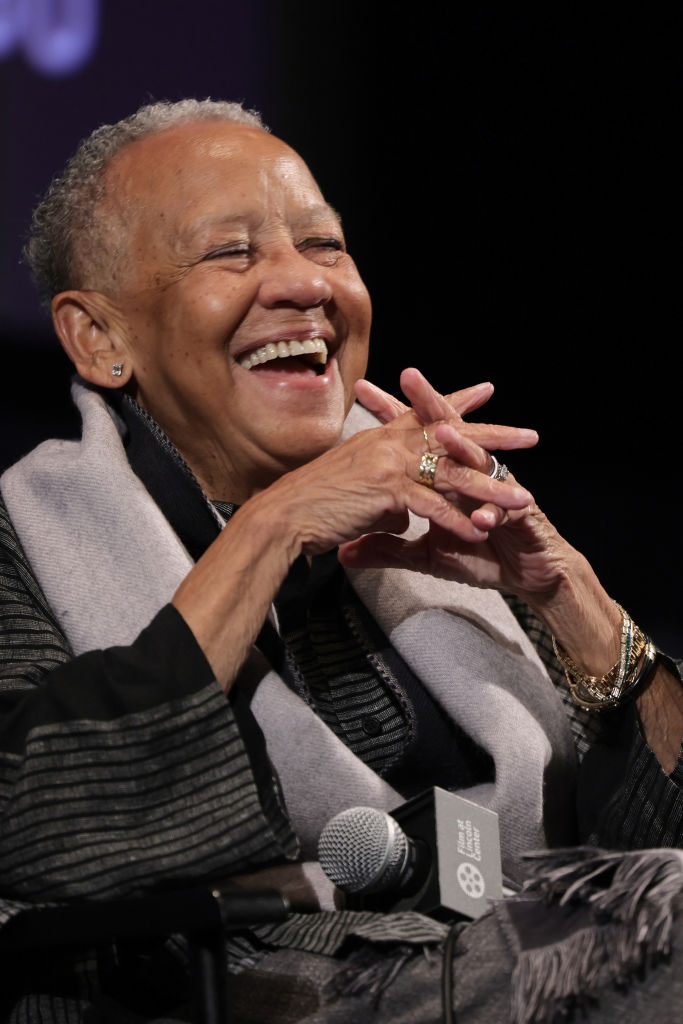

This is how I remember Nikki Giovanni: the quick and bright of her eyes and humor, her smile as wide and committed as the belief she had in us. Nikki died on Monday, something still too hard for those of us who don’t know a world without her to yet fully absorb. She was our national poet. Our national treasure. She was our professor and our friend. And she was all of these and more than these despite an America determined that said she’d be neither.

Nikki was a Gemini, born beneath the hard June 7, 1943 sun, and born upon the blood-soaked land called Knoxville, Tennessee. It was a city three driving hours from Pulaski, Tennessee, the city where the Klan was spawned in 1865. By the time Yolande Cornelia “Nikki” Giovanni Jr. took her first breath, more than 2,000 people were known to have been lynched across the failed Confederate States of America. Tennessee rounded out the top eight of the most lawless, racist, and deadly.

The terror and the tenacity that must have defined those who held hard memories of that land may have been mitigated for Nikki by the freedom waters of the Ohio River that flowed through the Cincinnati of her early childhood. Her parents, both educators, moved the family to Ohio for employment not long after Nikki was born.

Decades later, when I would come to her a little bit but for a long time, I heard the tenacity, but rarely the terror, save for the conversation we had in the spring of 2007 after a student she’d identified as troubling and frightening, shot and killed 32 human beings, wounded 17 others with gunfire, and a nation still able to be stopped and shocked by mass shootings.

In every other conversation we had, what I heard in her voice was intentional joy and hope. It spilled past overflow from the woman who was once a girl of 15 who returned to Knoxville and her grandparents for high school, Woman King style. She made her Ohio-Tennessee backstory, despite the violence at home and in the world, somehow work out well for her–and us.

The young Ms. Giovanni soared at what was then Austin High, Knoxville’s Black school. Nikki earned admission and the right to begin coursework at Fisk University, her grandfather’s alma mater, well before completing high school. At Fisk, there were early signs of who she’d become. Nikki started a literary journal at the University and the school’s SNCC chapter. She graduated with an honors degree in history in 1967, a little later than the rest of her class, because she was put on time out for protesting.

Like all women who choose to change the world, Nikki was a perfect storm of love and difficult.

Source: Michael Loccisano / Getty

And at every point, she was a poet, a role she embraced perhaps most fully when her beloved grandmother passed away. Instead of turning into herself in that space of pain, she turned outward toward us, inviting us on what would become an incredible 56-year, 30-book journey that began when she published her first collection of poems, 1968’s Black Feeling, Black Talk, and said,

“I’m into my Black Thing

And it’s filling all

My empty spots”

And when she offered one of the most quoted lines of verse written during the extraordinary Black Power and Black Arts period of the late 1960s and 1970s, Nikki reminded us in her poem, “Nikki-Rosa,” which many consider her magnum opus, that:

“Black love is Black wealth”

We knew her words then weren’t simply a beautiful turn of verse. They were a call to action. They were a mandate. They were a commitment–one that Nikki Giovanni carried the whole of her life, including on the day she met a 20-year-old, shy, insecure, unpublished, mostly secret poet who was me. And me, who saw the world then as a series of obstacles, never of opportunities.

Here’s what happened on the Upper West Side of Manhattan back when Black people still lived there.

Source: Jack Robinson / Getty

We were at a gathering called together by the mom of a college friend of mine. I went because I was asked to go, not because I knew I would be walking into something I learned was pretty normal for him: a room full of Black stars of the literary and high art world. And the brightest star in a room of fabulous creators and keepers of our culture, there was Ms. Giovanni, the brightest star of all. And me? I was the plus-one girl who was repeatedly asked to say her name “just one more time, please.”

It was after one of those understandable, gentle requests that the unthinkable happened.

The host, my friend’s mother, said lovingly and encouragingly to me and the room, “My son tells me this young woman is a wonderful emerging poet. So before our Nikki reads for us, let’s hear from you.” This was one of those moments when you prayed for the ability to disappear, rewrite the scene, or collapse for some unknown medical reason.

I rarely shared my poetry back then. I did with my mother and a couple of close friends–including the one who invited me to the gathering that day (only to betray me). Shy me standing there insecure and scared and with no way out. I had no choice but to pull out the notebook of poems I carried everywhere back then, assumed the position, and read my poem.

I don’t remember what poem or what it was even about. I don’t remember if it was good or not. I don’t remember if there was a polite sort of look at the baby applause or a belly-deep whooping from the women in the room.

But I remember the love Nikki showered on me. She did it then. She did it later, and she kept on doing it. Before I was published and at every turn after, there was Nikki. She blurbed my books and talked about the quality of my writing, not just the content, which was chock full of my life’s twisty truths back then that some appreciated only for what they thought was a sight-line into a Black freak show.

Not Nikki. She honored my writing and praised my fiction as much as she did my poetry and nonfiction. She strengthened me by giving me the specific sort of noticing that happens when a woman sees the world through Toni Morrison’s Black Lens. Each time we talked, she brought to life those words from decades ago–that call to action, that mandate and commitment: Black love is Black wealth.

That’s what I remember most from that day in that home on the Upper West Side when the Upper West Side was still, and I was still 20. And that’s what I remember from the conversations and years that followed the first meeting. I remember that those words became foundational to my work–to my humanity. With varying degrees of success but never varying degrees of commitment, I carry her mandate into every room I enter.

Source: The Washington Post / Getty

Nikki Giovanni: Poet, writer, professor, wise woman, mother, wife, lover, daughter, sister, fighter, and friend. You who insisted on hope, on truth, on wisdom, on possibility, on joy and on light for a people born into a nation uncommitted to us knowing any of those: we will keep your fire lit.

We will pass that fire on.

We will remain forever grateful for the roadmaps to freedom we found in your poems and your woman-to-woman words.

We will remain forever grateful for having been able to be with you in real-time and space.

We will remain forever grateful that because of these gifts, because of you, beloved sister, master teacher and creator and artist for the ages, culture creator and artist for the ages, we will forever be able, despite rough waters, to simply remain.

SEE ALSO:

7 Nikki Giovanni Poems That Will Lift Your Spirits

Freedom Quotes To Keep Black People Strong And Hopeful

[ione_media_gallery id=”3022774″ overlay=”true”]